How do you quantify your running fitness?

Is your running getting better or staying the same? Why? For your most recent half marathon or marathon, did you meet your goal? How did you set your goal? Was it realistic based on your current fitness? Often when I ask these questions, I get some pretty vague answers. Fortunately there are some easy tools to help you:

- Assess your current running fitness level

- Establish constructive training paces to optimize your running workouts

- Estimate a realistic race goal based on your current fitness level.

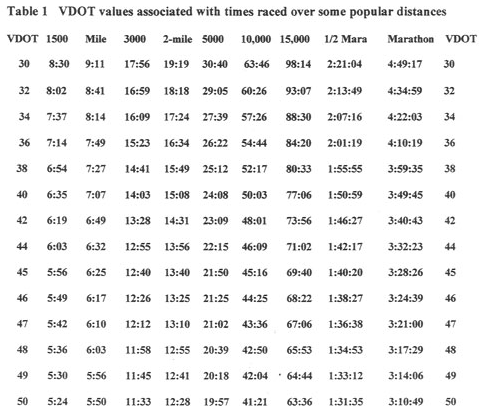

Although there are several assessment & training programs out there, one of the more recognized and widely used approaches was developed by a famous running coach, Jack Daniels. He worked and studied runners for years and has published several books on proper training pace strategies. The basic theory is that people have a specific cardio capacity which determines how much oxygen your body can process and utilize, and is referred to as VO2 max. Typically this is measured in a lab tracking your oxygen consumption as you run on a treadmill doing a ramp test. Daniels felt this type of testing was impractical for most people and that running economy (i.e. your running form) was also a factor in how runners performed. Efficient runners could run at a faster pace with lower oxygen consumption than an inefficient runner. He combined both VO2 max and running economy into one factor he called VDOT. He tested well conditioned runners at varying distances in race conditions (going as fast as they possibly could) to create predictable VDOT values. For example, if your VDOT value was 46 you should be able to run a 5k in 21:25, a half marathon at 1:38 and a marathon at 3:24. This isn't saying that if you only train to maximize your 5k time that you can go out and run a sub 3:30 marathon, but rather with your existing cardio capacity and running efficiency, that you are capable of running a sub 3:30 marathon with the proper amount of endurance training.

The following link is a great short summary of Daniel's work, consisting of four parts. I'd recommend reading all four sections, as it provides a quick but effective overview of his book.

First takeaway... you can do a running assessment by simply doing a 5k race at 100% effort. As an alternative, you can do a 5k on your own or even on your treadmill (using 1% grade and plenty of fans). In either case, you should ensure you are doing effective warm-ups and cool downs to maximize your performance and recovery. Generally you want to have good testing conditions including cool temperatures, a flat course and low wind to minimize the impact on the results. After giving it 100%, the assessment is simply seeing where your 5k time lines up on the VDOT chart.

from the table above, if you ran a 5k in 22:15, your current VDOT (running fitness) would be 44.

Second takeaway... running fitness is built over time training at optimal training paces / zones. The problem is that people often train without using specific zones and end up doing "junk miles" or training in the "black hole" where the paces are too fast to most effectively build aerobic endurance or too slow to effectively build aerobic power.

So, how do you use the VDOT tables and values and avoid "junk miles"? You can use the tables on page 4 of Daniel's summary or an online calculator like the one found here. I like using the online calculator as it does the interpolation for you (for values that aren't whole numbers). Using this calculator, you simply enter your 5k time and it will give you your VDOT value and your specific training paces. A critically important point to understand is that you train at your current paces, not the paces associated with your goal VDOT value. Most coaches recommend about 80% of your weekly volume needs to be at the Easy race pace, with the remaining 20% being speed work. Typically this would be Interval running at the Interval pace or Threshold running at the Threshold pace (to state the obvious). Utilizing a well-designed "polarized" training program combining higher volume low intensity training with shorter duration high intensity training has been shown to maximize VO2 max gains.

After 6 to 8 weeks of training you will need to assess your fitness again by doing another 5k or run test. If you have created and executed a good training plan, you will see a faster 5k time and a higher corresponding VDOT value... so you have a clear indication of running fitness gains. Once you've demonstrated that you are ready for faster training paces by doing a faster run test, then you can readjust your training paces with your new VDOT value and begin the process again for another training block... that's how fitness is built.

Example:

Let's say you go out and run a 21:00 5k and plug it into the VDOT calculator discussed above, and it will give you a VDOT of 47.0. This tells you for training your running zones are:

Z1 (Easy/Long) 8:39 - 9:12 pace - focused on building aerobic base

Z2 (Marathon) 7:40 pace - Marathon pace (theoretical / ideal pace).

Z3 (Threshold) 7:13 threshold pace - This is the theoretical pace you can maintain for about an hour, with ideal conditions.

Z4 (Interval) 6:37 mile pace.

Z5 (Repetition) 6:13 for track workouts (with corresponding paces for 400/200).

An interval workout may look something like:

- 1 mile warmup, Z1

- 8 Sets of:

- 1/4 mile at Z4

- 1/4 mile at Z1

- 1 mile cool down at Z1

A tempo/threshold workout may look something like:

- 10 minutes warmup at Z1

- 3 Sets of:

- 5 minutes at Z2

- 5 minutes at Z3

- 3 minutes at Z1

- 11 minutes cool down at Z1

A long run may look like:

- 4 miles at Z1

- 3 miles at Z2

- 1 miles at Z3

- 4 miles at Z1

Personally I believe it's good to do some race pace-specific training in longer runs to help build adaptations to that specific pace, assist with your race day pacing feel, and break up the monotony.

These are just very general examples of different run types you could do, but you will need to develop a specific training program designed to meet your overall racing goals. Note that you still need to focus around 80% of your total running at that EZ Zone 1 pacing, so typically you'd have more runs done during the week focused on those EZ paced efforts. By varying your interval, threshold and rest durations, you can slowly increase your intensity each week to gradually increase your overall running load and associated fitness.

The third takeaway... by using my VDOT numbers I can establish realistic targets for upcoming races based "equivalent pacing". The VDOT chart plots what a well trained runner at a given VDOT value is likely to run across the varying distances. Using the original example, if your VDOT is 44 and you've done the appropriate distance training, you should be capable of running a 1:42:17 half marathon. Realistically, it is often difficult to hit these longer run targets for a couple of reasons. The first is that testing is often done in more ideal conditions such as a treadmill, a flat course, cool day, low wind, etc. that may not reflect your specific course or conditions on race day. The second is that the data was based on runners putting in sufficiently high volume to end up with a very flat fatigue curve (or critical pace/power curve) meaning they have very solid endurance. I'll talk about this in an upcoming article, but even some locally elite runners I've tracked in Athlinks (running sub 16:00 5k's and sub 2:40 marathons) have difficulty hitting the marathon equivalent VDOT targets. Many coaches derate the VDOT values from the chart between 1 to 1.5 VDOT points for a half marathon and 2 to 3 points for a full marathon. For our example above, this would project a realistic equivalent half marathon pace for a 44 VDOT runner to be to 1:45:25 to 1:44:23. Getting adequate volume to meet the longer VDOT values is even more of a challenge for triathletes, who are likely training with lower running specific volumes than traditional running-only athletes. This doesn't take away from the value of the equivalent paces, it's simply a matter of making some adjustments to establish achievable targets.

Final Thoughts:

Note that not everyone uses the same Zone concept (i.e. Friel uses different zones) so when talking to others, other people may refer to a Jack Daniels/VDOT Zone 1 (Easy/Long) as Zone 2 aerobic base. It's very important to understand the basis for calculating zones before simply applying it to a training plan. Look to the zone descriptions to give you a bit of guidance for comparison.

I read a great quote that said, "Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful." (George E.P. Box, statistician). Again, there is some variation in individuals, but overall I've found the VDOT strategy very effective at helping with running fitness assessments, building training paces, and projecting realistic race times (with modifications). Most importantly, when used correctly, VDOT is an effective tool for building running fitness and speed.

Train smarter, not harder.